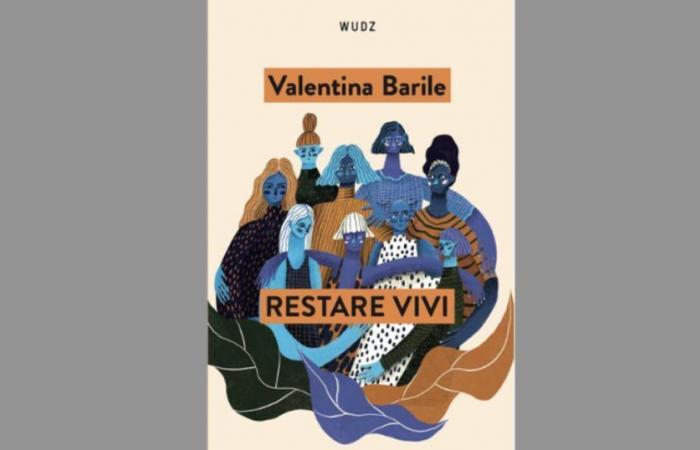

“Always be able to feel in the depths of yourselves every injustice committed against anyone in any part of the world”, I thought of this phrase from Che Guevara when I met the journalist Valentina Barilein the bookstore with Stay alivepublished by the newly formed and fighting publishing house Wudz.

A “small dictionary of resistance”, as the subtitle mentions, which not by chance boasts the premise of Aleida Guevara March, Che’s first daughter, who asks herself about the book: “Will you know how to be sensitive faced with the harsh truth told in these pages? I hope so”. This is because “Staying alive” forces us to keep our gaze precisely where we don’t want to look and it does so with the strength of a writing dry who knows how to talk about suffering without ever indulging in desperation.

The book is a journey into the “drug corridor”, a strip of land in Colombia where farmers, feminists, shamans, drug traffickers and guerrillas have been at war for sixty years. A war that has millions of deaths and millions of disappeared. And as Barile herself says, in the prologue of the book, what remains of this journey is the pervivenciaa word that brings together women and men who “live fighting for themselves and others, in silence or loudly, against the State, guerrilla warfare and drug trafficking”.

A word that represents the determination not to get used to injustices, in a country where people die without even knowing why, but where there are men who fight every day to keep alive the memory of those who are no longer here by asking for truth and justice. The same truth and the same justice they are asking for Mario Paciolla, found dead in Colombia on 10 July 2020, where he worked for the UN to enforce the peace agreements between the government and FARC guerrillas. A case that seems to be of more interest to Colombians than to Italians, given the new request for archiving of the case by the Rome prosecutor’s office.

One word perhaps encapsulates the meaning of this work: pervivencia.

The living beings I met in Colombia are all gods pervivientesand I say living beings because those who resist armed conflict and illegal trafficking are not only humans, but also animals, trees and all living creatures: the natives forcibly transferred, deprived of their territories, killed, wild animals sold together with smuggled timber, gold, coltan, and mining in general. The sense of pervivencia, which encompasses the political and social struggle of resistence carried out by entire communities, it therefore also involves non-living beings.

The last chapter of the book is dedicated to Mario Paciolla, what do you think of the new archiving request?

I think that behind the assassination of Mario Paciolla in Colombia there are dynamics, choices, actions that were unfortunately implemented because his work was effective but politically exploited, and the UN, an organization created to build peace between countries and peoples of the world, with the passage of time has evidently and practically lost its initial mission. The UN did not protect Mario from the macabre chessboard in which he found himself without perhaps realizing it, or rather, he had begun to understand it very well a few months earlier and even more so in the last anguishing week he lived before his body was found lifeless .

We don’t know if it was the organization that got him into trouble, as he claims Julieta Duque, the Colombian journalist who is investigating his assassination, or whether the organization itself still failed to protect him from someone or something. In short, the UN has something to do with it. It’s all too clear. And the fact that in Italy, the Rome prosecutor’s office decided for the second time to dismiss the case after just over six months after its reopening had been requested again is truly surrealbut most of all disheartening because it is an international case that must be treated first of all with professional seriousness.

What do you miss most about those places and those people?

The places and the people. The harmony that exists between living beings. The attention, the care, the feeling. Time that seems to expand because adapting to the unexpected becomes fundamental. It is not possible respect work plans, meetings, appointments, deliveries because we don’t know whether or not it is possible to reach a village or a city at the pre-established, scheduled times, for infinite and varied reasons which may be meteorological, security, diplomatic between civil society, institutions and armed groups. That staying alive despite the pain, that hope that nestles in the word pervivencia, which is explained very clearly by Aleida Guevara March, in the preface.

What did you learn from this trip and what do you think you left these people?

Those who do the job of writing have a very important task, that is to put aside their own personality and become half through which to convey the reality he observes, what happens before his eyes or what his gaze and legs go looking for. As a journalist I believe I left in their hearts the hope that their pain would be shared miles and miles away; This is the only thing I can do, unfortunately. That the pain told and the ransom and the justice they are waiting for can reach the other side of the ocean and reach that Western society that is still so far away, despite social media and active global citizenship.

What I have the privilege of cherishing instead are grace and grace teachings that they gave me and that I learned from the people I met and who guided me during the journey.