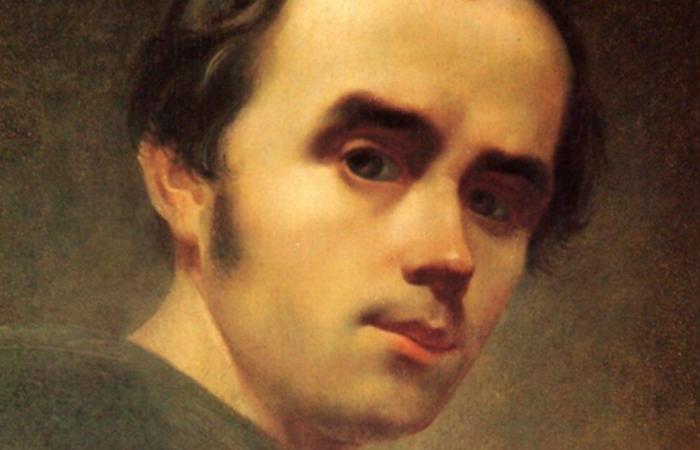

Taras Shevchenko born in 1814 near Kyiv in a family of serfs. Orphaned at a young age, he begins to wander from one village to another, carrying out the most varied jobs. Meanwhile he attended country schools for short periods, run by deacons and clerics: he learned to read and write and became passionate about drawing. Entered service with the nobleman Pavlo Enhel’hardt, follows him first to Kyiv, then to Vilnius. In 1831 he arrived in Petersburg, then the capital of the tsarist empire, where he was placed in an art studio so that he could become a servant-artist (1). Here comes the fact that he will change his life: Ivan Soshenko, a fellow artist from his country, was enthusiastic about his artistic talents and introduced him to illustrious figures of the time, including the painter Karl Brjullov and the poet Vasilij Žukovskij, who in 1838 managed to redeem him from servitude: the sum necessary for the redemption was reached thanks to the sale of a painting by Bryullov.

As a free man, in May 1839 Shevchenko was able to enroll at the Academy of Fine Arts, which he attended successfully. Furthermore, he dedicates himself to reading with a self-taught spirit. He ranges from art history (Vasari) to ancient history (Plutarch), to the masters of European literature (Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, Hugo).

The Petersburg stay is a lot fruitful for the education of the young person. He frequented the most fashionable salons, the most renowned clubs, and met the personalities of the time. He can assimilate the democratic and libertarian spirit that hovers in the Russian society of those years. Serfdom (2), sadly known to the young Ukrainian, it is the question that agitates much of the Russian intelligentsia. He reveals literary talents and also dedicates himself to poetry. In the 1840 his first poetic collection comes out Kobzar [Il menestrello] (3). The following year, more of his poems appeared in the almanac «Lastivka» [La rondine]. The works that mark ševčenk’s debut are unanimously hailed as the genuine expression of a rare poetic talent. However, the majority of Petersburg critics regret that they are written in Ukrainian.

In 1845 Shevchenko he finishes the Academy, specializing in engraving and etching. Among the most famous paintings stand out “The Gypsy – Sorceress” (1841, watercolor), “Kateryna” (1842, oil), “Peasant Family” (1843, oil), the series of etchings “Pictorial Ukraine” (1844).

Having returned to his native land, he found employment at the Archaeographic Commission. This activity leads him to travel throughout Ukraine: he must identify objects, monuments and buildings of particular artistic value. In 1846 he met the historian Kostomarov, who introduced him to the Cyril and Methodius Society, a secret political group, which fought for a spiritual and political union of the Slavic peoples, all equally free and independent, for the recognition of Ukraine as an autonomous nation. In the 1847, following a police search, the company is dissolved. Shevchenko was arrested and transported to St. Petersburg, where he remained in prison for two months. Inspired by this experience, he wrote the cycle “V kazemati” [Nella casamatta]. Sentenced to compulsory military service in Siberia, the poet is sent under escort first to Orenburg, then to the Orsk fortress. These are terrible years: he can withstand the frost and heavy work thanks to his robust temperament. Despite the ban on writing and painting, Shevchenko continues to dedicate himself to poetry: he carries, hidden in a boot, a notebook of verses.

In 1857, after the death of Tsar Nicholas II, thanks also to his influential St. Petersburg friends, the ten-year exile of the Ukrainian poet was able to end. He returns to the Russian capital, where he spends the last years of his life. He frequents the literary environment, meets the novelists Turgenev, Goncharov, the democratic critic Chernyshevsky. It came out in 1860 Kobzar in a new edition. Struck by a long illness, he passed away in March 1861.

Taras Shevchenko rises from a humble serf to the dignity of a national poet, he scores the literary and cultural rebirth of all its people. He is a brilliant self-taught man, whose poetry is the most genuine expression of popular culture, which he certainly got to know during his childhood spent in the fields and villages. He therefore represents the transition from oral tradition to written literature.

1) In the Tsarist Empire it was normal for a nobleman to train one or more servants to have actors or artists available. 2) Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in 1861. 3) Kobzar, a minstrel who accompanies the singing with the kobza, a sort of Ukrainian eight-stringed lute.

PG

***

Imprisonment is burdensome, even if,

in truth, I had no freedom.

However we lived somehow,

even if in a foreign field…

Now we have to wait

that bad luck, like a god,

and I await it, I am on guard,

I curse my evil intellect,

who deceived fools,

suffocates freedom in a puddle.

It makes my heart cold to remember that

not in Ukraine I will be buried,

that I will not live in Ukraine,

I will love people and the Lord.

[Tra il 19 e il 30 maggio 1847, San Pietroburgo]

***

My thoughts, my thoughts,

you my only ones,

at least don’t abandon me

in the evil hour.

Arrive, my pigeons

with gray wings,

from the wide Dnipro

to the steppe for walking

with the miserable Kyrgyz,

they are now miserable,

now bare… And free

they still pray to God.

Come, my dears,

with quiet speeches

I will greet you, like children,

and I will cry with you.

[Seconda metà del 1847, Fortezza di Orsk]

***

The sun sets, the mountains are black,

a little bird becomes quiet, the field is silent,

happy are the people for rest,

And I look… I fly with my heart

in a dark little garden, in Ukraine,

I fly, I fly, I think a thought,

and the heart seems to rest.

Black the field, the forest, the mountains,

a star comes out in the blue sky.

Oh star! Star! – and the tears flow.

Maybe you have already arisen in Ukraine too?

Maybe the brown eyes are looking for you

in the blue sky? Maybe they forget you?

If they have forgotten, may they fall asleep,

so as not to hear about my fate.

[Seconda metà del 1847, Fortezza di Orsk]

***

It was my thirteenth year.

I was grazing sheep beyond the village.

Perhaps the little sun was shining,

Maybe I had something?

I was so happy, happy,

as if in God…………

They called me to eat,

and I was standing in the weeds

to pray to God… And I don’t know

because then as a child

I prayed with great pleasure,

why was I so cheerful?

The sky of the Lord, the village,

the sheep seemed to rejoice!

And the sun was burning, not burning!

But not long did the sun warm,

I didn’t pray for long…

Everything burned and turned purple

and heaven blazed.

As if awakened, I looked:

the village was blackened,

even the blue divine sky

he had turned pale.

I looked at the sheep –

the sheep weren’t mine!

I turned towards the houses –

I didn’t have a home!

God had given me nothing!…

And the tears flowed,

burdensome tears!… A girl,

right on the street,

Not far away, next to me,

chose hemp,

he heard me crying.

he approached, greeted me,

he dried my tears

and kissed me……………….

It was as if the sun was shining,

As if everything in the world were

mine… the fields, the woods, the gardens!…

And we, jokingly, led

other people’s sheep to water.

Chimeras!… and even today, if I remember,

the heart cries in pain, because

the Lord has not left me

live a short life in that paradise.

I would have died, plowing in the field,

I would have known nothing in the world,

I wouldn’t have been a weirdo in the world,

I would not have cursed people and God!

[Seconda metà del 1847, Fortezza di Orsk]

***

Oh, I’ll look, I’ll see

that steppe, the field;

Merciful God will not give perhaps

freedom for old age.

I would go to Ukraine,

I would go home,

they would greet me there,

rejoicing for the elderly,

There I would rest a little,

praying to God,

There I… Don’t even think about it,

nothing will happen.

But how do you live

in hopeless captivity?

Teach me, good people,

otherwise I’ll go crazy.

[Prima metà del 1848, Fortezza di Orsk]

***

If I had shoes,

I would go to the dance.

My pain!

I don’t have shoes,

and the music plays, plays,

it instills sadness!

Oh, I will wander barefoot in the field,

I will seek my fate,

my luck! Look

me with black eyebrows,

my lying fate,

I’m unfortunate!

A little girl at the ball,

with the red shoes, –

I’m worried.

Without pomp, without love

I hold my black eyebrows,

I hold them by serving!

[Seconda metà del 1848, Kos-Aral]

***

I fell in love,

I got married

to an unfortunate orphan –

such is my fate!

Proud, bad people

they separated us, they had me

taken and taken to a shelter –

they gave me to moskal’!

And, lonely woman

Muscovite, I’m getting old

in a strange house –

[Seconda metà del 1848, Kos-Aral]

such is my fate!

Derogatory term used to refer to Russian soldiers.

***

My mother gave birth to me

in the tall buildings,

wrapping me in silk.

In gold, in velvet,

hidden like that little flower,

I grew, I grew.

And I grew up wonderfully:

brown eyes, black eyebrows,

the white face.

I fell in love with a poor man,

my mother did not allow me,

I stayed

to live as a spinster in high buildings

spinster all my life, –

my misfortune.

Like a blade of grass in the valley,

I am in solitary solitude

getting older.

I don’t look at the divine world,

I don’t turn to anyone…

But the elderly mother…

Forgive me, my mother!

[Seconda metà del 1848, Kos-Aral]

I will curse you, until

I won’t be dead.

***

On Easter day, on the hay,

facing the sun, the children

they played with colored eggs

–

they began to boast about the gifts.

They had one for the holidays

adorned with an embroidery the blouse.

They had bought that one

a ribbon, a bow to another.

To whom a hat of Agnina,

horse leather shoes,

to whom a large cloth. Only one

sat with nothing to smooth,

An orphan, with little hands

hidden in the sleeves.

– Mom bought it for me.

– Dad fixed it for me.

– And my godmother

[Prima metà del 1849, Kos-Aral]

he embroidered a frieze. – And I had lunch with the Pope, –

Said the little orphan.Colored eggs are traditional for Orthodox Easter(“krašanky”).