Because remake cinema is not in crisis: the problem is that we can’t stand the idea that the new one could be better

There is a precise moment, now recurring, that accompanies every announcement of a remake: not the release of the trailer, not the first images, but the judgement. It arrives immediately, often before the film even actually exists. “It wasn’t needed”, “the original was untouchable”, “yet another nostalgia operation”. It is an automatic, almost reflex reaction, which says much less about cinema and much more about how we have learned to watch it.

The remake, today, has become the perfect scapegoat. It doesn’t matter what genre it touches, what audience it wants to intercept or what language it uses: it is perceived as a symptom of creative tiredness, or worse laziness, as if cinema had suddenly stopped telling new stories. But this reading is superficial, and above all historically short-sighted. Cinema has always remade itself (the late Sidney Lumet even said so). He has always reworked myths, novels, previous films, stories already told. The difference is that we didn’t once live in a cultural ecosystem dominated by constant comparison, the infinite archive, and hyper-aware nostalgia. Today every remake is born already condemned to be placed next to a memory, not a work.

And this is where we start to look bad

In recent years we have seen remakes arrive which, regardless of their final value, have tried different paths. Some have chosen aesthetic fidelity, others have shifted the thematic center of gravity, still others have changed tone, audience or sensitivity. Yet the debate that surrounds them rarely goes into the merits of these choices. It stops first. It runs aground on the emotional comparison with what we remembered. When a remake takes a beloved story, the most common question is not “what is it trying to say?”, but “why isn’t it how I remember it?”. It is an understandable but profoundly limiting yardstick, because it transforms cinema into a museum and not into a living language.

We expect a contemporary film to recreate exactly the effect that a work from the past had on us in another moment of life, with another gaze, another context, another age. It’s an impossible request. Yet we continue to use it as a critical parameter.

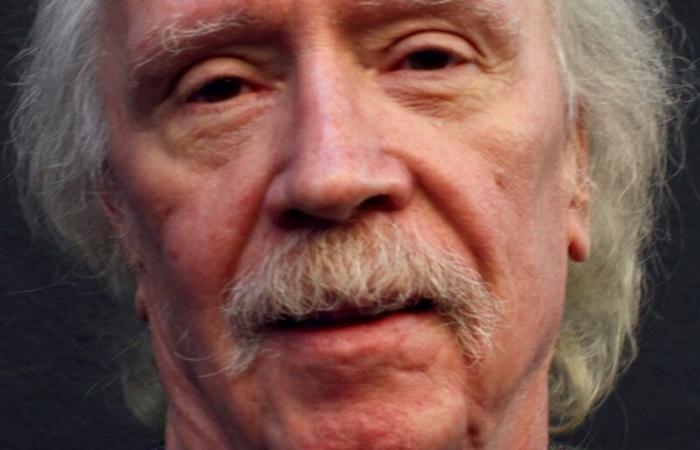

The history of cinema, however, sensationally proves us wrong. Scarfacetoday considered an absolute cultural icon, is the remake of Scarface (1932), that no one defends with religious fervor anymore. The modern version didn’t just replicate a plot: it rewrote the sense of power and excess for another era, speaking a language that the original couldn’t yet have. The 1983 version was so successful that typing “Scarface” into Google for the good version Howard Hawks is bitterly buried by Montana played by a certain Al Pacino. The same goes for The Thing (The thing1982 – by John Carpenter), initially rejected because it was too far from the most reassuring The Thing from Another World (The thing from another world1951 – by Christian Nyby), and today considered one of the greatest examples of paranoid horror ever made. He did not respect the original: he surpassed it, precisely because he dared to betray it.

Even more radical is the case of The Fly. Here the remake doesn’t just work better: it makes the 1958 original (miserably translated into Dr. K’s experiment) almost superfluous, because it uses that story as a vehicle to talk about the body, illness, decomposition and love with a depth that didn’t exist before. In these cases the remake is not an operation of recovery, but of cultural rewriting. And no one today dreams of saying that “it wasn’t necessary”.

This leads to an inconvenient truth: it’s not true that we hate remakes. We hate the idea that they can succeed better than the original. Because this undermines a reassuring dogma: that the value of a work is fixed forever, linked to the moment in which we loved it for the first time. Accepting that a new version can be more effective means accepting that our gaze is not the definitive unit of measurement of cinema.

The real distinction, then, is not whether a remake is necessary, but whether it has a point of view. Many fail not because they exist, but because they don’t dare. Because they limit themselves to reproducing the surface of the original without questioning its profound meaning. But when a remake actually tries to re-read, update, or even contradict what came before, then it becomes interesting even when it gets it wrong.

When the remake really fails (and not due to nostalgia)

Having said that, we need to be equally clear: yes, there are remakes that are objectively pitiful. And the reason for their failure is as instructive as the success of the best cases. Because it shows that the problem is not the remake itself, but the total absence of a vision.

Psycho, at Gus Van Sant, is the most emblematic example. It is not remembered as a disaster because it betrayed the original of Alfred Hitchcockbut because he didn’t have the courage to do it. It is an almost surgical replica, a copy without any expressive need. It demonstrates a brutal truth: remaking an identical film is not an act of respect, but a void of meaning.

It is even more paradoxical The Lion King. Technically impressive, emotionally anesthetized. In an attempt to make everything “more real”, the film sacrifices the expressiveness, theatricality and symbolic strength that made the original animation memorable. Here the remake does not reread: he replaces one language with another without understanding what he was losing.

The case of Oldboy it’s even more revealing. Not just useless compared to the original of Park Chan-wookbut deeply misunderstood. It transports a culturally and morally specific story into a context that cannot support its weight, emptying it of ambiguity and ferocity. Here the problem is not “redoing”, but not understanding what is being done againand then if the patch is taken by someone like Spike Leeit makes even more noise.

These remakes fail not because they dare too much, but because they never dare. They are afraid of disturbing the public, of taking sides, of betraying the original. And they end up producing films that do not dialogue with the past, but ask it for permission to exist. A remake without a point of view is destined to be forgotten, because it has nothing to defend.

Are we the problem?

Then there is an aspect that is rarely admitted, perhaps the most important: we spectators have also changed. We watch films already knowing how they will be discussed, memes, dismantled online. We come prepared for disappointment, often eager to confirm it. This defensive attitude does not protect the original, it fossilizes it. And it prevents the new from breathing. We celebrate the successful remakes of the past, but we deny the present ones the right to fail, to grow, to be reevaluated.

This is not about absolving the industry, which often plays it safe and confuses memory with value. But not even to dismiss every remake as a cynical operation. Cinema hasn’t become less creative, it’s simply become more exposed. Every attempt at rewriting occurs under a lens that amplifies reactions, simplifies the discussion and reduces everything to a quick verdict.

Perhaps the point is not to defend remakes, nor to attack them. Maybe the point is to go back and look at them for what they are: films that exist in the present, with their own limitations, their own obsessions and their own possibilities. Not competing versions of the past, but imperfect dialogues with it.

Cinema doesn’t die when it repeats a story. It dies when we stop listening to what that repetition is trying to tell us.