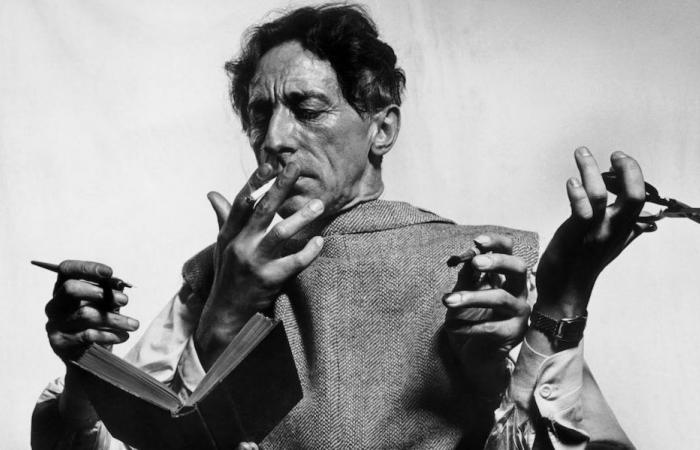

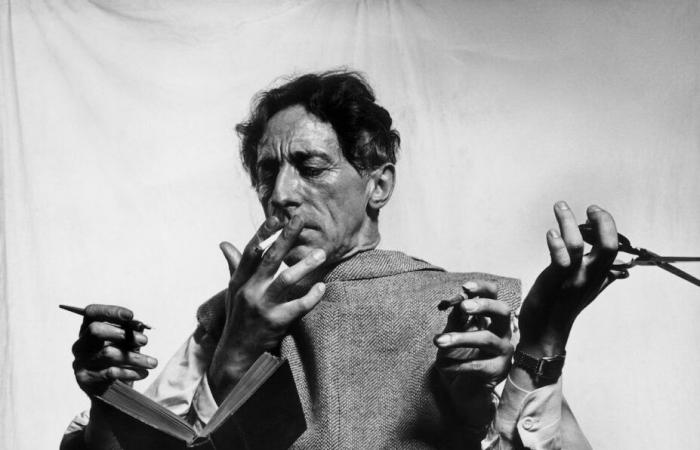

A six-armed juggler who juggles various tools – a pen, scissors, a brush and a book – while undauntedly smoking a cigarette: this is how photographer Philippe Halsman immortalizes Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau for “Life” magazine in 1949, revealing the multifaceted talent but also the versatility of the French writer, designer and director. There Peggy Guggenheim Collection of Venice dedicates a major retrospective to the artist which takes its title from the well-known portrait, Jean Cocteau. The juggler’s revenge. Open until 16 September 2024, the exhibition presents over one hundred and fifty works from public and private collections that mark the salient moments of his career. Through his creations which range from graphic works and drawings, to books and film productions, to tapestries and jewels, the curator Kenneth E. Silver reconstructs Cocteau’s imagination in the rooms of Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, underlining how “the suffering for art, drug addiction, obscenity, scandal… are aspects of the myth (and real life) of Jean Cocteau”. Defined by his contemporaries as enfant terriblefor his controversial relationships with Hitler’s favorite sculptor, Arno Breker, or for his past addiction to opium which he made no secret of, as documented by the various drawings which translate the symptoms of withdrawal from the psychoactive substance into visual form on the body and mind, (Opium – The torments of abstinence, 1928-1929). His multifaceted inspiration, at the time a source of criticism, tends to escape the meshes of the rigid classifications and stylistic constraints of the time. Cocteau defines himself as a poet, but he is also a critic and a prolific author of theatrical texts.

On display are some of his best-known volumes, from the 1910 edition of the collection of poems Prince Frivolouspassing through the story The Terrible Boys published in 1929, up to what is considered his most autobiographical work, The White Book. Printed anonymously for the first time in 1928, the short novel reveals Cocteau’s interest in his own sex, opposing the open condemnation of homosexuality in the Paris of the time, despite abstaining from public admission all his life.

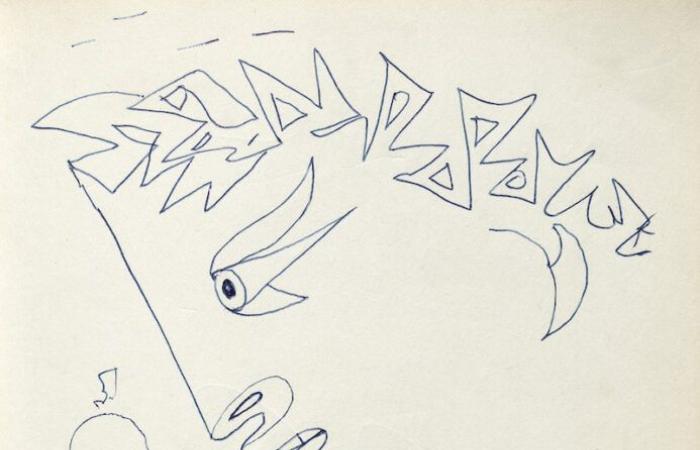

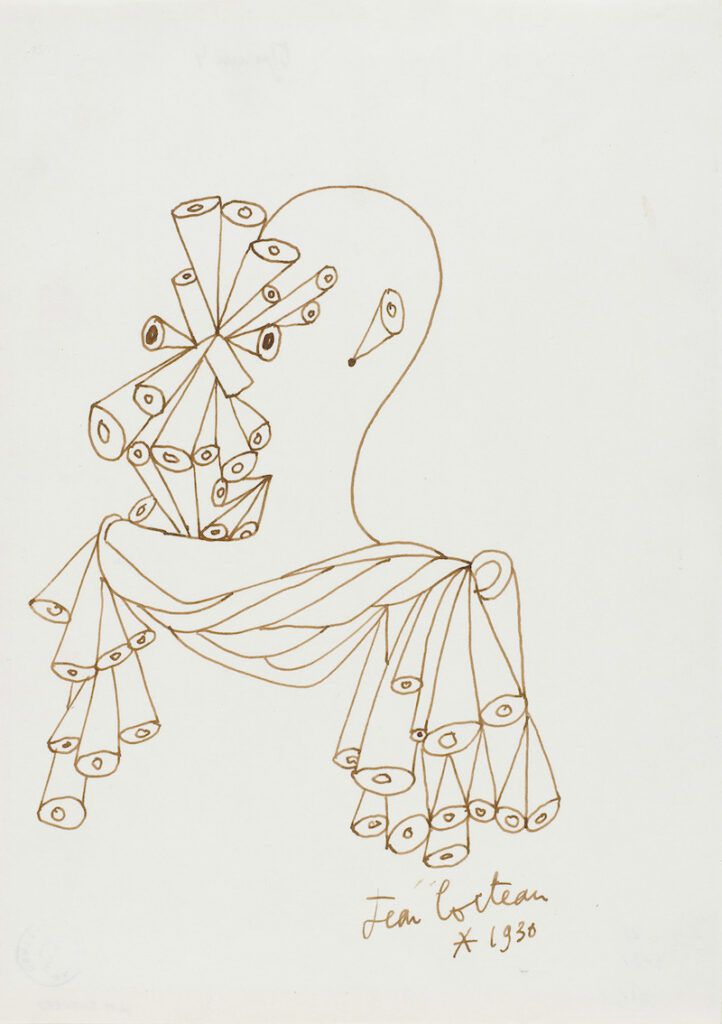

The second edition of 1930 includes a series of illustrations that reveal the artist’s ability to master different expressive techniques. The drawings and studies that precede them visually describe the feelings and erotic experiences of young men who abandon themselves to passion. A theme of homosexual love that returns in other works, including Pair of sailors (1947) or Two Men Embracing (1951), where the characters are explicitly depicted in the moment of seeking pleasure. Already in the 1920s, the interest in pederasty in ancient Greece had brought Cocteau closer to classicism. The study of the proportions of human anatomy in Greek statuary is visible in various sketches, such as in the revisitation of Laocoon (1932-1935) where the artist represents the Trojan priest no longer surrounded by sea serpents sent by the gods to kill him but by a rope that encircles his imposing body. However, the many incursions into the ancient world reveal a contradictory and anachronistic, at times grotesque, aspect, such as the rereading of the myth of the Bacchae (Bacchanals 1925), where the figures, decidedly caricatural, give in to the most ephemeral vices, becoming inebriated with libations, music, dance and eros. The classics represent for Cocteau a strong source of privileged inspiration, a common thread of his artistic production, since the rewritings of the Greek tragedies, including theAntigone by Sophocles which he staged in 1922 with the collaboration of Coco Chanel for the costumes and Pablo Picasso for the scenography. The exhibition presents the evocative masks worn by the choir that Cocteau creates using commonly used materials, such as pipe cleaners, beads or buttons. But it is above all the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice that attracts the artist who will create several film adaptations of the story throughout his career. The mirror, a central element in the Orphic legend, becomes the subject of the first room, creating a dialogue between Cocteau’s own works, from the extract from the 1950 black and white film to the The Mirror of Orpheus (1960-1989), and an analogy with Untitled (Orpheus, twice1991) by Cuban artist Felix Gonzales-Torres who, according to the curator, exemplifies the interest that contemporary queer artists have in the work of the French master.

Cocteau also looks to the present, therefore to the avant-gardes of the early twentieth century, creating numerous portraits of affiliates and exponents of the world of art and entertainment. He draws a funny pornographic caricature of the writer Tristan Tzara, depicts the painter Pablo Picasso sitting at the Café de La Rotonde, or the stylist and costume designer Elsa Schiaparelli wearing one of her iconic dresses. To accompany the portraits often only sketched on paper we find a series of photographs that immortalize Cocteau together with colleagues and friends, such as the actor Jean Marais at the Caffè Florian in Piazza San Marco, or the director Roberto Rossellini in a gondola in Venice, where spends long stays.

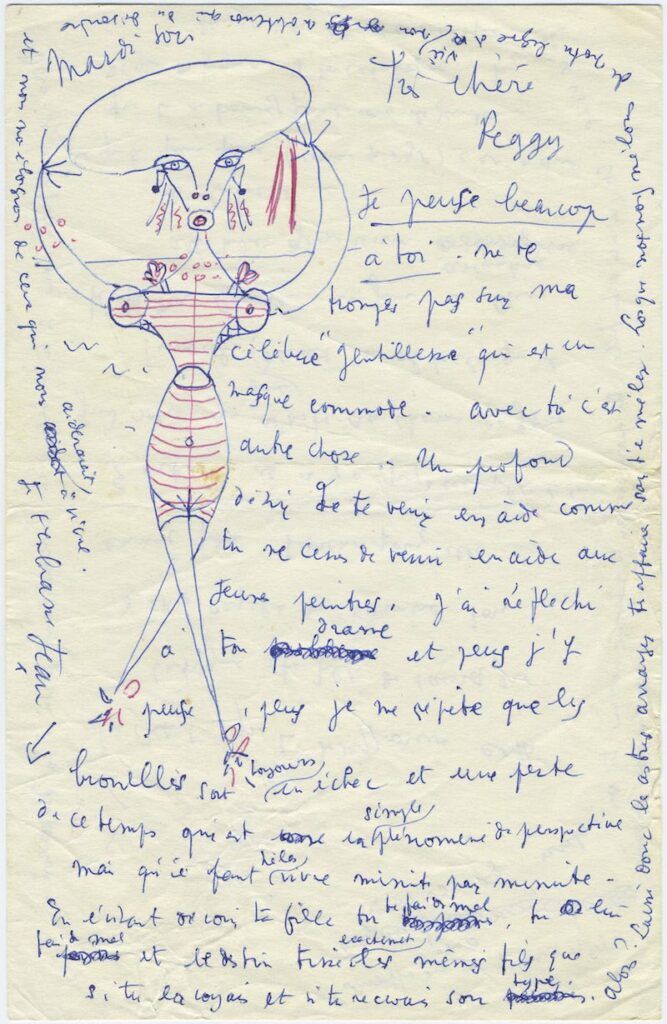

Cocteau describes Venice as a sort of city of dreams, and the evocative drawings he creates convey the very essence of the lagoon landscape; the artist captures the lights breaking in the water of the canals, its majestic architecture such as the Basilica della Salute (1959) or the Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore designed by Andrea Palladio. His relationship with the city was consolidated thanks to his friendship with Peggy Guggenheim, a visionary American collector who in 1938 had invited Cocteau to exhibit in her London gallery, commissioning the work from him Fear gives wings to courage (1938). Blocked by British Customs, the large drawing depicts an allegorical subject that was censored for its unequivocal promiscuity in representing the nude. In the last rooms the artist’s register changes; although the production maintains its distinctive trait, the design veers towards the Hollywood kitsch of those years; in fact Cocteau, dedicating himself more and more to popular culture and the mass media, transformed his art into a brand. It is probably no longer the hand of Cocteau but rather his studio that conceives the works which include various objects, from sculptures to jewellery, the result of collaborations with international designers. Moreover, Cocteau writes that “the privileges of beauty are immense. It also acts on those who do not notice it”, underlining how in his poetic universe the verbal and visual aspects are inextricably linked, one mirror of the other.