The Vuitton Foundation in Paris is hosting a large and beautiful exhibition by Gerhard Richter until March 2, 2026. Everything is there, in good order, well displayed and well presented in the sections and individual works. A truly exemplary exhibition. Richter is a very famous artist, I believe also among a large audience. It has been defined as the European, or German, version of Pop Art, because it began at the beginning of the Sixties, more decidedly critical of the commodity and consumer society than the Americans, also returning to figuration by taking images from magazines or in any case photography.

I visited it in the company of Riccardo Panattoni, philosopher, who, director of the “Tiresia” research center of the University of Verona, had invited me to a study day focused on the book On painting by Gilles Deleuze (already reviewed here by Massimo Donà), which would be the day after our return, so it was in our thoughts and conversations. For my speech I had thought of the work of Luca Pancrazzi, whose triple exhibition in progress in the three locations of the Marcorossi gallery, in Milan, Verona and Turin (until 31 January 2026), I had just seen, interviewing the artist to review it on this site. During the visit to Richter’s exhibition I noticed some aspects that compare them and my thoughts intertwined with each room.

Richter’s work really seems like the perfect illustration of Deleuze’s book. It’s worth rereading On painting leafing through a Richter catalogue, step by step: chaos, catastrophe, grey-germ, diagram, colour, modulation. The exhibition significantly begins with a “failed” painting with angry black brushstrokes scribbled over an underlying attempt deemed unsuccessful. It’s the catastrophe. First there had been the chaos of the Informal, which Richter now wanted to overcome. The passage occurs, as in Deleuze, through grey, of which Deleuze, with reference to Paul Klee, distinguishes a dull and dead version, greyness, from a living and decisive one, in which the colors already vibrate. This second gray is the paradigm that allows the leap – this is how it is described, again following Klee -, not an order, but the origin itself, retroactive, after the factas they say in French, of painting in its specificity, in its form, in its color.

Thus Richter passes to gray and at the same time “returns” to figuration, but it is a return sui generis, retroactive precisely, precisely because it is based on a derived image, that is, taken, as mentioned, from photographic sources. Photography acts as a bridge here. A decisive bridge, because it changes everything, painting changes, which loses its specificity in the modernist Greenbergian sense of the term. Here we move away from Deleuze.

Since then, Richter has practiced painting and photography simultaneously, so closely that we could speak of a double medium. Richter will say it with one of his famous phrases, apparently clear and actually ambiguous enough to appear mysterious: “I photograph with painting”. What does it mean to photograph with painting, if you are actually painting photographs? It means precisely that the two should no longer be distinguished, they are a medium only thanks to their considered indissoluble bond. So Richter paints photographs, first in gray and then in color, reworking the image, as you will remember, by going over it with a large brush while it is still wet, making it appear “blurred” – a photographic term and peculiarity. Then he returns to abstraction, and then the color explodes together with the elaboration, spatula strokes, flashy brush strokes, scratching and so on. But these paintings also involve a “blurred” part.

So first he blurred the image then he blurred the painting. Sometimes he rephotographs parts of them and “copies” them by enlarging them again in paint. He photographs close to the details of his paintings and turns them into a photographic book. Then he passes abstract painting onto photographs and in short he no longer separates them. Until the last period, in which he dedicated himself to drawing, and through it brought into play other photographic effects that we could define as more “unconscious”, from the optical unconscious.

Thus Richter has represented since the Seventies, but even more so since the Eighties, the champion of a whole progeny of artists who have remade photographs into paintings with various intentions. Now, it is enough to compare this work on mediums to the pure simulation relationship of the hyperrealists of the 1960s and the Pictures Generation of the 1980s to understand what is at stake: not competition, not simulation, to summarize, but a real reworking of the image and rethinking of the medium.

If this is the formal path, that of the contents represented opens another important chapter. There has been much discussion about it, especially referring to theAtlasor rather the collection of clippings and photographs that Richter has built – and I emphasize built – for decades. A sort of archive, however, it is also a work diary in which everything is intertwined again: the historical images (the portrait of his uncle in Nazi military clothing is famous, and the cycles on the Bader Meinohf and the stolen photographs of the Nazi concentration camp) are joined by those that have attracted his attention (the candles, the skulls), the private ones (the wives, the children), those of details of his paintings, as indeed in his work. But what is striking in the parallelism is not so much the mixing of the subjects as the coming and going that messes up the linear chronology, which shows a Richter who retraces his steps, resumes and develops, and then continues and again resumes even further back. Not for nothing on several occasions – not on this Parisian one, unfortunately – Richter exposed theAtlas same in large panels. It is the archive which, as a result of re-elaboration, becomes form and becomes a work among works, or a work of works.

But what seems most important to me in this way of proceeding is that the internal development of the artistic work on the one hand has repercussions on the memory of history and biography, on the other it proceeds according to the continuous rethinking of what gradually develops on what has already been done, in a path of constant renewal. We always start again from the present, but the past returns and is renewed ceaselessly.

Luca Pancrazzi also works in this way and it is one of his peculiarities. He too has a huge archive of various types of materials, a mixture of clippings and photographs taken by himself, thousands of them, especially of landscapes. There is no personal, biographical aspect, which is replaced by that of the artistic work, the atelier, the tools, the tables, the walls, the play of light and shadows in the room, the exhibitions. This gradually becomes the source of his paintings and, precisely, it returns as his development, his formal research proceeds, to take it up again and rework it. Thus we find the “horizons” over the years, first watercolored, then built three-dimensionally in maquettes, then drawn, both simultaneously and varied after years. The same goes for landscapes and other subjects.

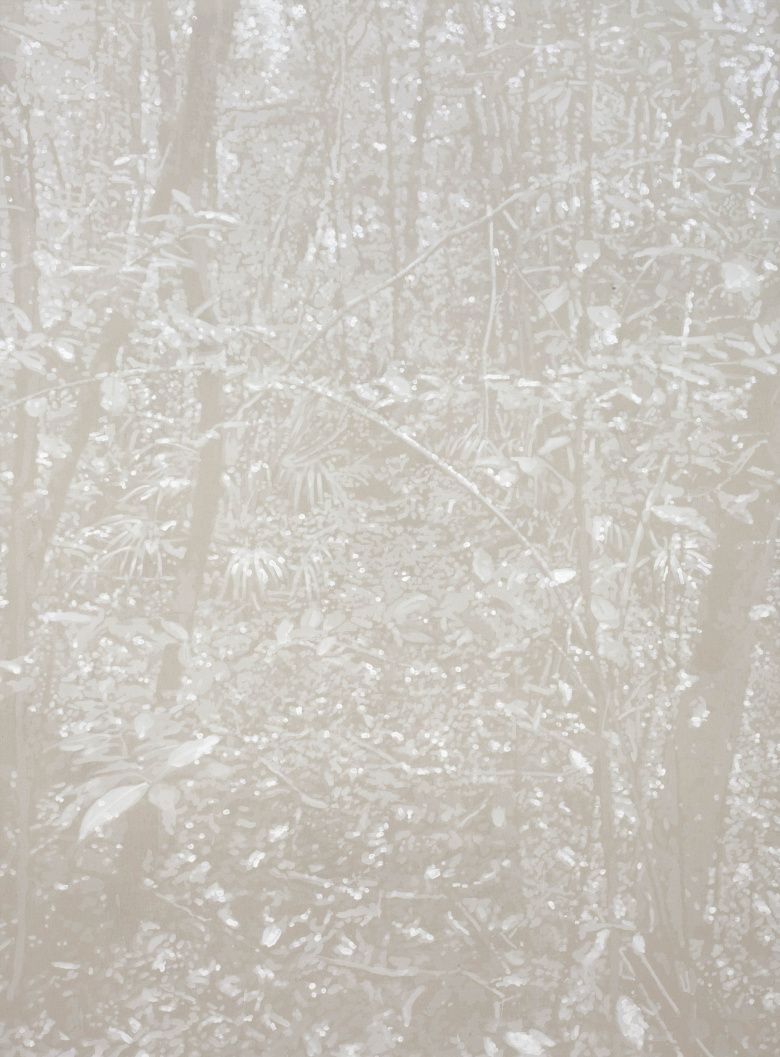

Thus in today’s exhibitions the subject of trees “returns”, already painted as part of the landscapes or in the shadows of those in front of the large windows of the atelier. The fact is that both in content and form the work has been renewed. As for the content, the singular title in Latin none other than suggests it: A city of trees. The landscape, the city, is now seen “from the trees”, both in the sense of being made of trees, almost born from the forest, and in that of being seen from or through them. The idea for the title in Latin, says the artist, comes from the fact that plants are scientifically classified with Latin names. “So this title shifts the question onto plants and would like to inaugurate a reversal of vision from subjective (human) to that of the plants themselves,” says the artist. “It is now the plants that observe and judge our lifestyle and, fascinated by our frenetic activity, they have not abandoned the cities but would be ready to take them back in a short time if only we let them do so”.

It is a typical asymmetrical reversal of Pancrazzi, the logical “paradigm” of his entire work, which he calls “variable variable symmetry” to indicate that in the symmetry of opposites there is always contained a difference that allows variation, and indeed recovery. Thus the landscape seen from the trees is not the pure symmetry of nature as opposed to the city: it is an alienating point of view that opens onto otherwise invisible analogies and differences. Among them, in particular, I think the theme of the tangle of branches is highlighted here, which reflects on that of the vision of the city. Pancrazzi had in fact, in the new themes, reached the question of intricacy, of its aspect of randomness, which had repercussions on a brushstroke that he defined as “stochastic”, random, unstructured.

It is as if he had returned to the “catastrophe”, to return to Deleuzian terms and discourse. In fact, it remains to be said that the paintings are – and have been for some time, as is now a stylistic feature of Pancrazzi – painted with white, only with white. It is his “germ colour”, but, like Klee’s grey, in his case too there are different whites. There are those who have understood it as the absence of colours, those as their sum, those who have understood it as non-colour, achrome. Pancrazzi’s white is another. In fact, it comes from the whiteboard, the one used to erase errors and rewrite over them. This is how the error, the discard, the correction enters the scene, again not as the opposite of the exact, of the necessary, but as what Pancrazzi summarizes with the expression, often the title of entire series, “out of register”. The data is relevant, it seems to me, even in rethinking, aesthetically if not philosophically, painting, as well as photography and their relationship.

Even in Pancrazzi, white gives rise to the explosion of color and its modulation. As can also be seen in the exhibitions at the Marcorossi galleries. In fact, the white paintings are contrasted with symmetrically varied paintings on paper, all colored. The novelty is that they are indeed taken from photographs but created freehand, no longer with the help of projection, a significant variation, because it brings into play the hand, the main character of painting, as Deleuze himself continues, that is, here the random component of the sign, the stroke, the brushstroke. Finally, this randomness, from stochastic, seen from the side of the trees, as indicated, represents a chaotic development yes, but in the sense of “natural”, and this both for the image and for the painting, and for the work, the history, the biography.

As for the photography, these paintings have a numerical series written at the bottom, which also constitutes the title, which at first glance appears random, but is actually deciphered as the complete recorded end date of the painting’s creation, almost as if it were a shot, a snapshot. And in a certain sense it becomes so, exactly.

On the cover, Luca Pancrazzi, 1304230320252025.