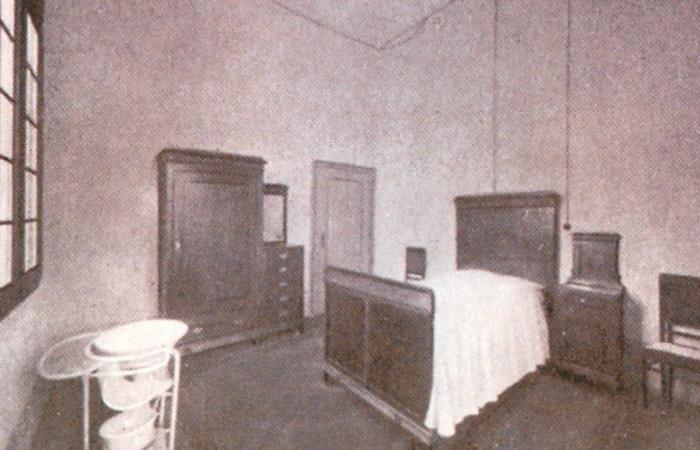

One of the rooms of the former Sant’Artemio psychiatric hospital in Treviso. Photos by: Tony Nardin, Francesco Turchetto, Laura Cacciolato

“When the unspeakable comes to light, it is political” the book by journalist Valentina Furlanetto opens with this powerful quote from Annie Ernaux One Hundred Days I’m Not Coming Back – Stories of madness, rebellion and freedom (Laterza, 2024). And from the first pages we understand that we are faced with an unusual book: it could perhaps be defined as an ‘unidentified editorial object’ or an essay that reads like a novel, halfway between journalistic investigation and memoir familiar.

In fact it is the fruit of Furlanetto’s in-depth research on a century of history of psychiatry in Italy, which tells of “one hundred years of questions” that is, those that the author asks herself to unravel the tangle of two parallel lives. The narrative is in fact driven by the lives of two people who had very different destinies, but both had as their backdrop the great social and legislative changes of the Italian twentieth century.

One life is that of Franco Basaglia, a revolutionary psychiatrist who fought to have mental asylums closed and whose birth marks the centenary this year. The other is that of Rosa, Basaglia’s peer and the author’s grandmother, a simple woman who experienced first-hand the transformation of psychiatric institutions before and after the reform of law 180 of 1978.

“I seem to see these boys, Franco walking with novels and school books under his arm through the streets of Venice, and Rosa walking on the side of the road returning from the factory, both with the thoughts one has at that age: a love, friendships, the future.”

Furlanetto’s book manages to be at the same time a very well-documented historical essay, but always easy to read, and a delicate testimony of what it means to live with mental suffering. One page after another, the reader delves into the heart of mental distress and the different responses that society has tried to offer through various treatment devices. From the age of great internment, where the main function of mental hospitals was that of custody, to the advent of shock therapies and psychotropic drugs, up to the deinstitutionalization and liberation of those who had been branded ‘crazy’. This last phase has Basaglia as its protagonist and the many people who followed his example and helped him carry out a real revolution (doctors, nurses, politicians, activists…) that is, one that finally restored dignity to psychiatric patients, until then deprived even of civil rights.

The two parallel but profoundly different lives of Franco and Rosa are reconstructed by Furlanetto through careful excavation of the sources, consulting laws, scientific texts and medical records – especially in the archive of the former Sant’Artemio psychiatric hospital in Treviso, where his grandmother had been hospitalized several times. The title of the book was born precisely from this painful family affair: “I haven’t been back for a hundred days” is the phrase that Rosa repeats to one of her daughters when she secretly visits her in a mental hospital, because having her own mother committed is a source of shame .

The book therefore takes us through a century in which Italian society changes profoundly, and with it also the approach to mental distress. The history of psychiatry reconstructed by Furlanetto shows how theories on the causes of mental illnesses and therapy proposals are strongly influenced by the sociopolitical interpretation of what ‘madness’ and ‘normality’ are.

The culmination of the story narrated is the approval of law 180, which opens a season of great hopes, yet the author does not limit herself only to celebrating its successes but also addresses the critical issues still present in the field of mental health. Already in the 1980s and 1990s, with the gradual closure of psychiatric hospitals, the initial enthusiasm gave way to the daily struggle of the families of former patients with undersized public services and a chronic lack of resources. Furthermore, Furlanetto registers concern for the difficulties in implementing therapeutic practices that respect patients’ rights (such as physical restraint which unfortunately is still widely used, for example in compulsory health treatments) and the spread of the “chemical asylum”. This definition is also the title of a book written by the psychiatrist Pietro Cipriano, in which he criticizes the sometimes too casual use of drugs as a panacea for any type of discomfort.

The language of the book is engaging and accessible, capable of bringing the reader closer to the complexity of the topics covered without exceeding in technicalities, and of making us reflect on how much work still needs to be done today to deconstruct the stigma that still weighs on those suffering from mental disorders.

In I haven’t been back for a hundred days, Valentina Furlanetto manages to build a bridge between past and present, inviting us not to forget the achievements achieved but also not to lower our guard in the face of new challenges. Among the many works published in this Basaglia centenary, her book is a significant contribution to enriching the debate around mental health, stimulating profound and necessary reflections.