On the eve of the last Oscar ceremony, the CEO of the powerful US distributor NEON Tom Quinn took part in a well-known podcast to talk about the promotional campaign for Anora by Sean Baker, which would soon defeat the competition and also win the statuette as best film of the year. Quinn pointed out that NEON had targeted Baker’s film, among many reasons, why it had a simply perfect ending. Awards like the Oscars are won when the film you promote is remembered by those who watch it and one of the most effective methods is make a good film that has a splendid endingcapable of leaving behind a tangible and positive memory.

Gallery

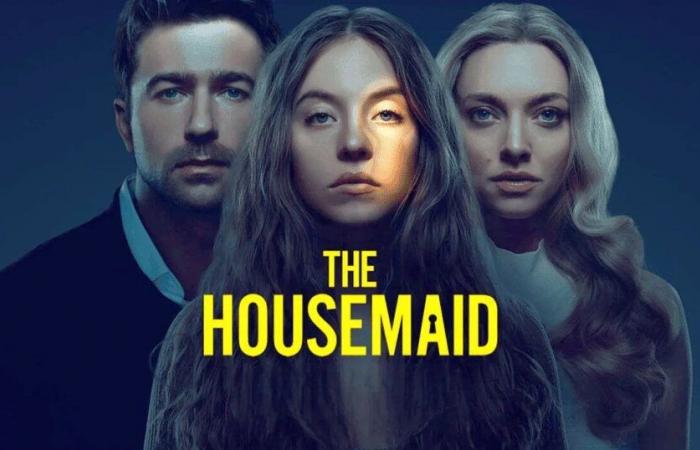

A B movie with a first class glamorous cast

One of the Family – The Housemaid does exactly that, taking Quinn’s advice literally. From Bridesmaids a A small favorthe director Paul Feig is building a small cinematic universe based on female protagonists with very distinctive traits, so trodden as to sometimes become voluntarily caricatured, often played by actresses who in turn enjoy a certain type of notoriety and who add, more or less directly, a further layer of glamor and gossip to B movies designed to provide entertainment without skimping on excess and exaggeration. Realism, verisimilitude or calmness are not part of Feig’s vocabulary, who prefers scandals, cat fights and conspiracies in a vast range of films ranging from comedy to thriller. Compared to the more recent A Small Favor, The Housemaid harks back to the pure thriller, so much so Rebecca Sonnenshine’s screenplay is insistently watchfulfor construction and tones, a Gone Girl by David Fincher. That type of approach and the division of the story into two distinct points of view (which review and sometimes overturn the meaning of certain events) are also present here, where the ambitions, however, are of a completely different kind, as are the tones and the degree of refinement with which the story is told.

Trad Wife vs Zoomer radicale

One of the family presents herself with an openness bordering on the catastrophic, which goes well with the situation of her protagonist: despite presenting herself as an excellent housekeeper with a lot of experience, Millie (Sydney Sweeney) is actually a young woman with no ties and no money, who exploits her appearance as a beautiful and harmless girl to try to find a job and maintain a condition of extreme precariousness, sleeping in the car, which is however preferable to the past from which she is trying to escape.

Getting hired byequally beautiful and blonde Nina (Amanda Seyfried) is a dream worth lying for and don’t pay too much attention to the neurotic delusions and outbursts of anger that the employer demonstrates right away. Millie and Nina are two recent evolutions of the political and social female imagination, which Feig and his screenwriter have the merit of being among the first to bring to the screen in a consumer film. Nina is the embodiment of translator, that is, the updated version for the second Trump term of the perfect wife and housemother who supports her husband, remains within the home, always goes around dressed in white and without a hair out of place, praising family values and dedicating herself to community activities related to her daughter’s education and dance recitals.

Millie is instead the restless incarnation of a generation Z without prospects, who does not hesitate to approach work and life from an amoral and personal perspective, aimed at extracting the maximum possible advantage, which is however barely sufficient for one’s survival and independence. As we discover her story, we understand that Millie has internalized and radicalized the most recent lessons of feminism or, to quote an old Sherlock joke, “he’s on the side of the angels but he’s not one of them.”

Millie is therefore hired to cook, clean the large Winchester mansion and take care of her daughter, receiving in exchange a cell phone, a small room in the attic to live in, food and salary. The assignment, however, turns out to be tortuous: Nina is as cunning and false as she is her relationships with her husband, daughter, mother-in-law and neighborhood friends are full of sinister nuances and unknowns. Furthermore, the housekeeper realizes that she feels an attraction for her husband Brandon (Brandon Sklenar), incredibly patient with his wife’s hysterical scenes and friendly with the new hire, who defends her from Nina’s often irrational, but not entirely unfounded, attacks.

The Housemaid gets off to the worst possible start, with a series of clichéd shots and dialogue so fake that it’s embarrassing. The film is quick to provide us with all the information necessary to introduce us to a story which, given the success Gone Girl achieved upon release, has at least a couple of predictable twists in the second half. The second half, however, is precisely the one in which the film shows its cards and dares more than the triangular tension between Millie’s attraction to Brandon and Nina’s hostility towards the employee. It is also the one in which the initial hitches are erased by an increasingly faster flow.

Amanda Seyfried and Sydney Sweeney have fun and enjoy it

Once again Feig isn’t afraid to resort to exaggeration and excess, seeking a continuous crescendo of tension and demanding a lot from its protagonists. Both prove perfect: Amanda Seyfried is great at throwing tantrums, basking in pure hysteria without ever losing control of the role. Together with The will by Ann Lee, the other film of the year which sees her in the role of an extreme and radical woman, although with a completely different register and ambitions, Family Home demonstrates how Seyfried knows how to portray roles of great intensity with naturalness and genuine enthusiasm.

We find Sydney Sweeney here after a difficult year on a personal level, surrounded by political scandals that have seen it become, more or less voluntarily, the face of a certain republican political narrative. The Housemaid arrives after an advertising campaign that made her radioactive for some of the public and after Christy, her “serious” film project which shattered at the box office along with her dreams of a leap in acting quality. Yet here Sweeney presents himself again as a sort of Hollywood unicum: an actress who is not afraid to use her sex appeal, but also to get her hands and reputation dirty, in commercial films which, year after year, see her as the protagonist and producer of one silent hit after another.

Upon closer inspection, his role is certainly not laudatory: Millie doesn’t come out looking great or a nice person. Yet she is the true protagonist of the film, which deliberately plays on the similarity of its very oxygenated protagonists, on the resilience and weaknesses that they both show and which, from a similar starting point, lead them to very different outcomes. The most tantalizing idea, the real coup, The Housemaid reserves it for the finale, which almost seems to transform the entire film into the genesis of yet another character with whom Sweeney is not afraid to pass, if not as a villain, at least as a woman as busty as she is disreputable, ready to be unpleasant and get her hands dirty when necessary.