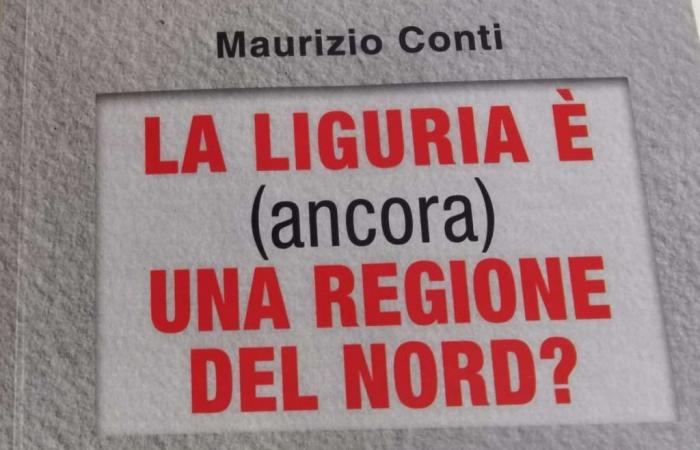

“Is Liguria (still) a Northern region?” is the title of Maurizio Conti’s book – full professor at the Department of Economics of the University of Genoa – published in recent days by Erga edizioni. And it is a question to which the author answers in the last pages of his work, after having examined a sufficient set of research, data and statistics: “The answer we feel like giving is yes: Liguria, fortunately, is still a northern region. It is above all due to the presence of various innovative companies in some sectors but also due to the existence of certain excellences in some fields of research. However It will remain attached to the North only if it manages to reverse course. Quickly. And to do this, as we have seen, a clear and broad-spectrum change in various public policies is necessary” (pages 283-284).

To reach this conclusion, Maurizio Conti examines the possible factors of decline (common to the country as a whole, although to a greater extent in Liguria than in the rest of Northern Italy): poor innovation, insufficient adoption of digital technologies and more efficient managerial practices: factors attributable to the dwarfism that characterizes many Italian companies. Small businesses have higher fixed costs associated with technological innovation than large ones and, being family-run, they tend to favor loyalty over ability when selecting managers.

Why this entrepreneurial dwarfism? What happened in Liguria? “The forty-year period 1980-2019, in particular the first twenty years, was characterized by important structural transformations in the Ligurian economy. In terms of added value, in 1980 industry in the strict sense (i.e. the manufacturing, extractive and energy sectors) produced at current prices just over 23% of the regional added value, construction 5%, the primary sector 3% and services 68%. Breaking down the services sector, the “services 1” sector (trade, transport, catering) produced approximately 31% of the added value, while “services 2” (financial and insurance activities, real estate activities, professional, scientific and technical activities, administrative and support services), approximately 22% with the remaining service activities, corresponding approximately to public administration, defense, school, etc., responsible for approximately 15% of the added value. (…) In the 1980s the process of structural transformation continued, so that in 1991 in Liguria the weight of industry lost another six percentage points and the “services 3” sector came to represent almost 21% in Liguria against 15% in the North: in other words in Liguria there has been a relative expansion of the State through the production of non-market services”.

In this process of deindustrialisation, the crisis of state shareholdings which played an important role in the region, and especially in Genoa, played a decisive role: if in 1971 there were 58 companies in Genoa with more than 500 employees, in 1981 they dropped to 50, for reach 31 in 2011.

The void left by the industry has only been partially filled by the growth of the tourism sector and port traffic. In this regard, Conti does justice to a cliché which, together with that of “small is beautiful” and others, has afflicted us in recent years. Tourism is not, as has often been said, “the oil of Italy”, in particular the South or Liguria. The creation of the expo area in the ancient port in Genoa was welcome, in our opinion. But it is a sector with low innovation, low investment, low, and necessarily largely non-permanent, wages. Paris, London, New York welcome important tourist flows but their wealth is certainly not based on them.

“Is Liguria (still) a Northern region?”, also in this regard is widely documented. However, awareness of the limits of this sector and the direction in which growth must be aimed is spreading. A few days after the presentation of the book, Mons. Marco Tasca, Metropolitan Archbishop of Genoa, in the speech given on June 24 in the Cathedral after the recitation of Vespers before presiding over the procession of St. John the Baptist, addressed the topic as follows: «… In Genoa the tourism sector is growing a lot, a peculiar vocation of our territory, for its history and for its naturalistic and artistic beauty. Nonetheless, it is crucial that other productive sectors are promoted, also with appropriate public investments, not only the industrial ones traditionally linked to the economic development of our city, but also – and above all – dynamic, innovative sectors. In this regard, the active role of synergies that are creating numerous new opportunities in particularly innovative fields (artificial intelligence, robotics, biomedical, etc.) is very positive… When business, administration, the cultural and university world all collaborate we will certainly benefit from it.”

The dream of the bishop of Genoa is «A city that is not only a pearl of architecture, landscape, lifestyle, not only an important administrative and industrial centre, but also a great laboratory for services and innovation”.

As for port activity, the author underlines its importance but also indicates its limits: the induced industry is no longer what it once was, and the port cities have to endure traffic congestion, oversized connection structures and the transfer to logistics activities of areas that could host activities more capable of creating value on site.

It is true, and not by chance in certain cities like La Spezia, where the port, not having the thousand-year-old tradition that it has in Genoa but having arisen almost ex novo, has long suffered a reaction of extraneousness if not rejection. Ports, in the absence of adequate policies, run the risk of imposing servitude on the cities that host them in exchange for benefits that go to the country system. It must also be kept in mind that in Genoa, a port also means industrial activity (ship repairs, shipyards, nautical refitting). And it produces tax revenues. Which, however, go to Rome. Over the years, right-wing and left-wing national governments have succeeded one another, measures have been taken to increase the (limited) possibility of self-financing of the Port Authorities, but still, little of the fiscal value generated remains in the territories that host the port structures.

Conti’s work, already full of data, is focused on the Ligurian territory but if we consider, for example, Hamburg, not only does it appear that its port is a source of employment, income and growth for the entire region, so much so that the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce and the Association of Entrepreneurs of the Port of Hamburg have called for greater commitment from the city and the federal government towards the port but we see that this generates around 1.5 billion euros in tax revenue for the metropolitan region every year. The federal government, in turn, earns up to 30 billion euros a year from customs revenue from the port alone (Dpa-AFX4, March 2024).

But let’s get back to the size factor. How can we push Ligurian companies to grow? On the one hand – explains Conti – improving the efficiency of public action could favor an increase in the size of companies, on the other hand regional industrial policies should be oriented to favor the dimensional growth of companies, even preventing unproductive companies, often very small and old, from remaining on the market. Because only innovative companies can grow. Therefore, it is necessary to promote innovation, strengthen the technological infrastructure and promote the adoption of advanced digital technologies in the production sector, invest in education and professional training, support competitive production sectors, which involves supporting sectors in which Liguria shows a comparative advantage, encouraging the growth of high-productivity sectors such as manufacturing and hi-tech services.

Stopping Conti’s decline is possible but not a given. We need “a redirection of industrial policies and regional training. However, and here the political side of the issue comes into play, the need for changes will clash, as it has already clashed in the past, with the social groups that, in Liguria, benefit from the status quo, as well as with the concentration in the very short term which has been characterizing much of Italian politics for years. On the contrary, the main beneficiaries of the reforms, young people, largely, as is logical, have difficulty identifying the advantages of policies which, in addition to generating relatively dispersed positive effects among a variety of subjects, also tend to materialize only in the medium term ”.

Thanks to the multi-sensory application of Vesepia, the reader will be able to access the updates of the data and studies that will be uploaded by the author, making this book a permanent research tool.