The art and its practices arise mainly as a communicative drive of great human themes, one of which is the mystery of death and its cults. The use of a less noble material such as cera it has not been reserved by man for mere practical matters – such as lighting, engraving tablets, ointments or waterproofing – but since ancient times it has taken part in funeral rituals as an element aimed at portraying faithful images on the faces of the deceased: the pictures of my ancestors. In ancient Rome and Greece it was customary to remember the deceased by making a cast of the face by pouring wax; this was then placed in wooden cases to honor his memory and carried in procession. Devotional it was too the use of wax in the Middle Agesa favorite element for the creation of votive offerings or relics of saints, widespread after the Crusades and brought from the East by pilgrims, custodians of enormous religious, symbolic and economic value. It is in the Renaissance that this material takes on true artistic and scientific potentialbecoming a privileged substance for modeling sculptural sketches, favored for its ductility and low cost. Vasari, artist and historian, in his fundamental text The Quick — narration of the history of art through the biographies of the artists — tells of the flourishing of wax heads in Florence in the fifteenth century and of the lost wax casting technique, already used in the Bronze Age, which allowed artists to obtain molds into which to pour the molten metal to create solid sculptures. However, it was in the 17th century that we witnessed a true golden age, with the profusion of anatomical ceroplasty: extremely realistic models of the human body, often disembowelled to show every little detail, more realistic than life. Created by great authors such as Gaetano Giulio Zumbo or Clemente Susini, these sculptures combined the very high precision and meticulousness of detail with an aesthetic and ecstatic significance worthy of a sublime work.

At the beginning of the twentieth century Aby Warburg and Julius von Schlosser, two art historians, analyzed its use, ennobling this technique and counting it among the great artistic forms. Warburg wrote the essay in 1902 Portrait art and the Florentine bourgeoisietaking an interest in the figurative forms of social and religious memory and recognizing in wax effigies a collective cultural function as well as a celebratory one. For Warburg, wax modeling was not just a demonstration or technical use, but the emblem of an embodied representation, oscillating between science and aesthetics. In 1911 it was Julius von Schlosser who continued this study with the text History of the wax portraita fundamental work for having recognized wax modeling as a form capable of mixing artisanal knowledge, image study and creative identity. Schlosser retraced its ancient roots, from funerary masks to religious and popular diffusion – especially in Emilia and Tuscany – recognizing it as an autonomous category of sculpture and placing emphasis on the ontological ambiguity of wax: it imitates flesh, but remains artificial, so much so as to question the boundary between reality and representation of the human being. This form of expression, which is not imitation but “the result of a psychological predisposition to the world articulated variously based on historical and cultural contexts”, is celebrated in Firenzeat the Uffizi Gallery, in the exhibition Once upon a time. The Doctors and the plastic arts. A journey of ninety works including sculptures, cameos and paintingslocated in the new exhibition spaces of the Western Wing, offers an in-depth look at the Florentine wax modeling collections between the 16th and 17th centuries. The exhibition, curated by Valentina Conticelli, Andrea Daninos and Simone Verdebrings together illustrious loans from museums such as the Bargello, Palazzo Pitti and La Specola, offering the possibility of seeing collected works of high forms of virtuosity, evidence of a largely lost art. Avidly sought after in the Renaissance to enrich the collections of noble families – such as that of the Medici – these works became obsolete during the Baroque, so much so that in 1783 Pietro Leopoldo di Lorena, Grand Duke of Tuscany, disposed of them at a large auction.

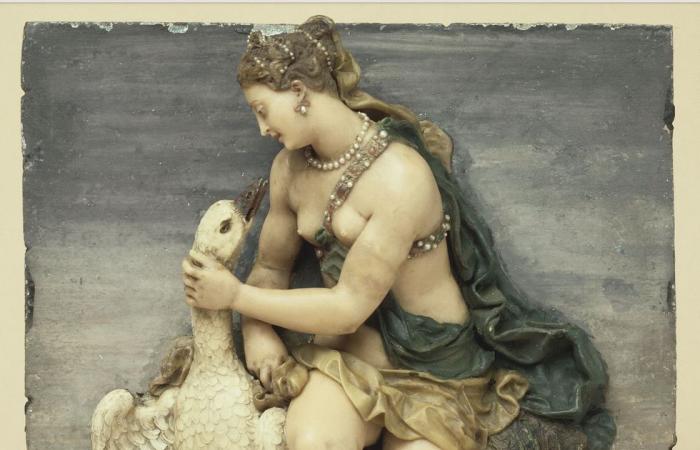

Once upon a time. The Doctors and the plastic arts it is a labyrinthine exposition which reveals, room after room, masterpieces such as the famous funeral mask on panel of Lorenzo the Magnificent, created in 1492 by the sculptor Orsino Benintendi, or the portrait of Francesco I de’ Medici by Pastorino de’ Pastorini, defined by Giorgio Vasari as the first example of polychrome wax. The complex composition created in 1571 by Giovanni Battista Capocaccia is of the same chromatic matrix, Pius V, Cardinal Bonelli and other cardinals witness the burning of the books on the Indexwhich with a refined technique depicts the prelate in front of the deposed Christ or in the presence of Saint Mary Magdalene; On display there is also another bas-relief of his, of a pagan subject, depicting a family – perhaps the Bonellis – coming from the famous collection of the merchant Frédéric Spitzer. The religious theme returns in the small jewels consecrated gods Agnus Dei from the mid-seventeenth century, wax medallions soaked in the baptismal font and made with the remains of Easter candles, imprinted with the symbol of the mystical Lamb and accompanied by other sacred images of Roman manufacture. Voluptuousness of forms and eroticism emerge instead in Leda with the swan by Martino Pasqualigo, known as Martino dal Friso, a sixteenth-century author who made forms palpable and carnal that until then had been mainly entrusted to two-dimensional painting.

A series of his portraits, such as that of Antonio Abondio depicting Maximilian II of Habsburg with a gorget collar, reveals an illustrious and widespread practice in the Renaissance, aimed at capturing profiles and physiognomies as precious memories, then also modeled on glass cameos. Also on display is a precious series of The latestfamous representations of the last things that man, according to the economy of divine providence, encounters at the end of life. Thus appear in chiseled ebony frames the tormented faces of the damned in the flames, those with their gaze turned towards the sky of the souls in purgatory and the angelic ones of the blessed in paradise: creations attributed to Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino which still testify to the double link between Church and power. This special investigation into wax and its noble and aesthetic application could only end with one of its greatest interpreters, Gaetano Giulio Zumbo, whose talent was supported by Cosimo III de’ Medici for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. His famous theaters in high relief are presented, depicting the plague epidemic of the seventeenth century that mowed down the Florentine population, the deposition of Christ and the corruption of bodies: rotting corpses in the tomb, with exposed viscera, which anticipate his extraordinary anatomical reconstructions now preserved in the La Specola Museum in Florence.

www.uffizi.it/gli-uffizi