Vittorio Sgarbi’s new book Arte e Fascismo (La nave di Teseo) is out today, dedicated to the artistic experience during the twenty-year period. On Friday, the author will be a guest at the 25th edition of the Milanesiana, conceived and directed by Elisabetta Sgarbi, for an evening entitled Arte e Fascismo. Nell’Arte non c’è Fascismo. Nel Fascismo non c’è Arte, a lecture by and with Vittorio Sgarbi, within the cycle “Rinascimenti e Scoperte” dedicated to the masters of art (Montalto delle Marche, Piazza Umberto I, 9 pm). We publish an excerpt from the book.

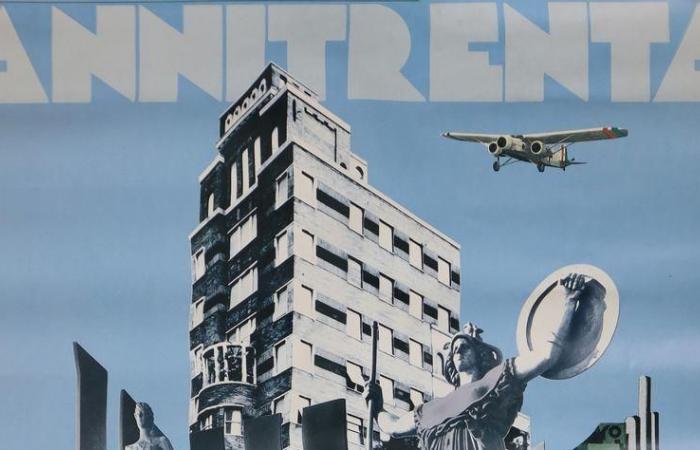

Reticence. Fear of history. Perennial anti-fascism. The Ghost of Mussolini. That is: one must be absolutely anti-fascist. From these diktats comes the removal in the last forty years of the evident connection of Art and Fascism. Thus, starting from the unrivalled exhibition of 1982 (with the title in decofascist characters) Annitrenta, in Milan at Palazzo Reale/Arengario defined as an “epoch container”, there followed unmistakable exhibitions with elusive titles, whose theme was however always and only the same: Twentieth Century. Art and Life in Italy Between the Two Warsin Forlì, in the museums of San Domenico, in 2013, curated by Fernando Mazzocca; Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics. Italy 1918-1943 , catalogue of the exhibition in Milan, Fondazione Prada, in 2018, curated by Germano Celant; The regime of art. Cremona Prize 1939-1941, in Cremona, Ala Ponzone civic museum, 2018-2019, curated by me and Rodolfo Bona; to which must be added the exhibitions, in the name of Margherita Sarfatti, at the Mart and at Palazzo Reale in Milan. The one in Forlì, after a severe pronouncement by the city council, changed the bold title Dux. The years of consensus , historiographically impeccable, to the generic, and not strictly Sarfattian, Novecento.

We are anti-fascists. We cannot pronounce that word, if not against. Despite the evidence, chronological and iconographic. The damnatio memoriae. Never fascism. Un-nameable. Unnamed. Despite the evidence. The attraction of evil. Fascism is like the mafia. It must only be opposed. And told? No, unless pretending to talk about something else. Evading. Alluding. Digressing.

But the theme – and the time – is that. No. Better to pretend. Let’s deceive the people. Let’s give them some doses of Sarfatti. And those who signed the “Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals”? Gabriele d’Annunzio, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Ardengo Soffici, Luigi Pirandello, Margherita Sarfatti, Curzio Malaparte, Ugo Ojetti. Let’s ignore this detail, let’s talk about it regardless. This is how we got to today, removing, turning our heads, censoring. A gap of twenty years, and a darkness of eighty years after. We are beyond the centenary.

So, after Il regime dell’arte in Cremona, I wanted to repair this forgetfulness, this hypocrisy. I had done it in Stupinigi with the frightening exhibition Il Male. I had done it in Salemi, tearing away from Corleone the museum of the mafia, proposed by the Rosselli Foundation, and rejecting the consolatory and restorative Documentation Centre of the anti-mafia activities. The mafia that existed can be toldwithout fear, and the museum makes it a dead, archaeological thing. In a museum, contemporary art also dies. Fear betrays knowledge.

Angelica and Luciana Giussani (a surname otherwise known for its vocation to good) understood this and called their successful comic Diabolik, not Ginko. It is well known, on the other hand, that bad makes news, good doesn’t. That children love weapons and play war. That madness generates creativity, and health is contiguous with gymnastics (for goodness sake, nothing wrong with that; but Juri Chechi is no van Gogh). And so I decided, without veils, without puns, without hypocrisy: Art and Fascism.

What is known, what is ours, very great artists, starting with Adolfo Wildt. But La Russa has busts of the Duce in his house. We will come to terms with that. They were also, in exaggerated numbers, in a museum, the Musa of Salò, by will of Giordano Bruno Guerri, who had the courage to give a direct title, under essayistic guise: The Cult of the Duce; the art of consensus in the busts and depictions of Benito Mussoliniand nobody protested, as had happened in the partisan Seravezza way back in 1997.